![]()

by

Frontiers in Robotics and AI

Research & Innovation

Learn

August 10, 2016

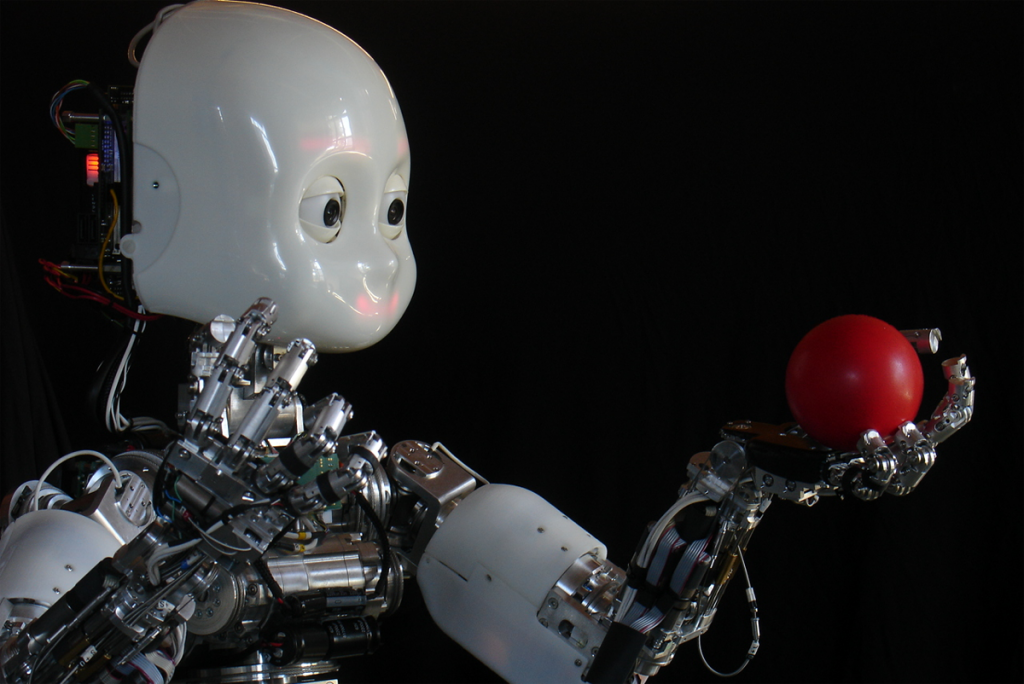

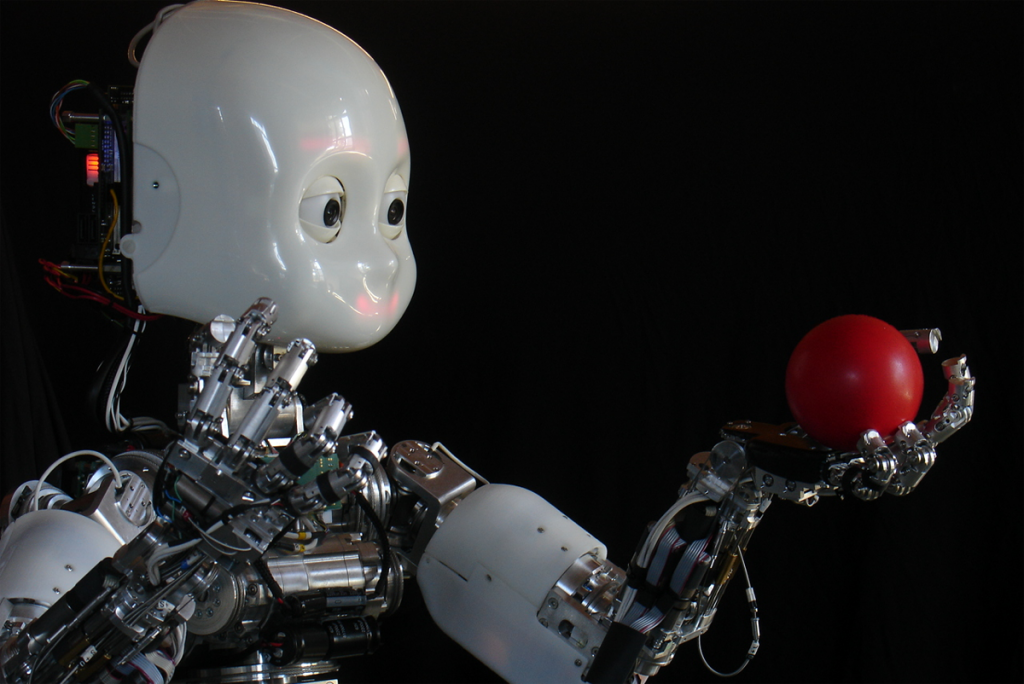

In this article, our humanoid robot iCub is put to the test using manipulation and interaction as sources of knowledge and new experience, as well as, providing a means to explore and control the environment. The design specifications of the iCub turn it into a physical container for neuroscience methods.

by Francesco Nori, Silvio Traversaro, Jorhabib Eljaik, Francesco Romano, Andrea Del Prete and Daniele Pucci

Back in 1961, the first industrial robot was operating on a General Motors assembly line. Its name was Unimate. It was fixed to the ground while it accomplished its task of transporting die castings and welding them on car bodies. More than half a century later, robots have come a long way, yet their most common use remains in that sector, for the most part, fixed to the ground (or some other part of the plant) almost caged away from humans as to not represent any danger. Interaction control (e.g., object manipulation) in these robots is usually achieved separately from whole-body posture control (e.g., balancing). If robots are thought to be present in our everyday lives and move in unstructured environments, interaction and posture control must be reconciled. A robot that can freely move in the environment is known as a free-floating base mechanism.

At the Italian Institute of Technology (IIT) in Genoa, Italy, we strongly believe in manipulation and interaction as sources of knowledge and new experience as well as means to explore and control the environment. A humanoid must then act on the environment to know it. The peculiar design specifications of our humanoid robot iCub turn it into a physical container for neuroscience methods. Our work takes advantage of its associated specificities and lays out the main building blocks that permit the implementation and integration of a system for balance and motion control of a humanoid robot. These components are namely, the low level joint-torque control, the task-space inverse dynamics control, the task-planner and contact forces and joint-torques estimator. These are seen as fundamental composing elements to effectively obtain such system on a real platform.

iCub is 104 cm tall and has 53 degrees of freedom: 6 in the head, 16 in each arm, 3 in the torso, and 6 in each leg. All joints but the hands and head are controlled by brushless electric motors coupled with harmonic drive gears. Custom-made Force/Torque (F/T) sensors are mounted in both iCub’s arms, between the shoulders and elbows, in both legs between the knees and hip and between the ankles and feet (see Figure 1). In addition, iCub is endowed with a compliant distributed pressure sensor (robot skin) composed by a flexible printed circuit board (PCB) covered with a layer of an elastic fabric further enveloped in a thin conductive layer. The PCB is composed by triangular modules of 10 taxels, which act as capacitance gages with temperature sensors for drift compensation.

As a general overview, our main goal is to keep our robot at a given configuration (posture) while being able to cope with multiple contacts. In order to do so, we first need to know where in its body are contacts happening, but not only! Also the forces and torques (a.k.a. wrenches) at those points are needed if we want to maintain contact stability (the robot skin gives us only the location of the contact). A robot can exert a particular force by making its DC motors provide the torques that generate a desired wrench at the point of contact.

The main components of this system are namely, the low level joint-torque control, the task-space inverse dynamics control, the task-planner and contact forces and joint-torques estimator. These are seen as fundamental composing elements to effectively obtain balance and motion control on a platform. In particular, the task-space inverse dynamics controller is used for finding those torques that satisfy the body posture and contact stability tasks knowing what the current joint torques are, along with the wrenches at the points of contact. Figure 2 shows the general workflow of the system.

Let us now give a little more of insight into the different blocks composing this framework. Contact wrenches on iCub are estimated, not directly measured. This is done exploiting the embedded F/T sensors and the skin, in conjunction with the velocity, acceleration and inertial information of the links. If the robot is treated like multiple branches cut at the location of the F/T sensors (see Figure 1), for each of them we can formulate Newton’s and Euler’s equations and solve for the unknown contact wrenches. An exact estimate for a specific branch of the robot is given when only one contact happens, otherwise the algorithm tries to give the best estimate possible for each contact among the infinitely many solutions. Once these external wrenches are known, this information can be propagated recursively to estimate also the internal wrenches (between links) and finally the joint torques. In this way, iCub does not need to use joint-torque sensors.

The joint-torque control block (in Figure 2) uses the estimated joint torques and compensates for friction to guarantee that each motor provides the desired amount of torque, as commanded by the task-space inverse dynamic control block.

All the elements that have been mentioned until now use values that are usually provided by a computer aided design (CAD) software, such as the links’ centers of mass or their mass inertias.

Special attention must be paid to these parameters, since they are usually not accurate enough, making the job of the task-space inverse dynamic control block much harder. A somewhat similar problem occurs in the low level joint-torque control block, since it relates through a mathematical model the voltage that must be given to the motors and a desired output torque, also taking into account the presence of friction. The amount of friction changes from one joint to another. The parameters that characterise friction (friction coefficients) and the dynamical parameters of the robot are thus identified and tuned. These are the jobs of the Dynamic model identification and the Motor Identification block respectively.

At this point we are left with the commander in chief, the Task-space Inverse Dynamic Control block. The framework that has been adopted computes the joint torques to match as close as possible the desired contact forces while being compatible with the system dynamics and contact constraints all tailored to suit floating-base mechanisms. This set of force tasks is assigned a maximum priority, while others tasks can still be specified as long as they don’t enter in conflict with the higher-priority tasks. In the case of iCub standing on the ground and interacting with its two arms, these tasks correspond to the right and left foot wrenches that regulate the interaction with the floor and similarly for the two arms, with a final postural task to maintain the robot joints as close as possible to a certain reference posture. These references are indirectly computed such that they follow a desired trajectory of the center of mass while the robot’s angular momentum is reduced. Figure 3 is a snapshot of iCub following a sinusoidal trajectory for its center of mass, while maintaining balance exerting the appropriate forces on the two points of contact, namely, its two feet. Figures 4 and 5 show the results of this double-support (two feet in contact) experiment on planar contacts.

For more information see the original research paper:

Nori F, Traversaro S, Eljaik J, Romano F, Del Prete A and Pucci D (2015) iCub whole-body control through force regulation on rigid non-coplanar contacts. Front. Robot. AI 2:6. doi: 10.3389/frobt.2015.00006.

Additional references:

Metta, G., Natale, L., Nori, F., Sandini, G., Vernon, D., Fadiga, L., von Hofsten C., Santos-Victor, J., Bernardino, A. and Montesano, L., The iCub Humanoid Robot: An Open-Systems Platform for Research in Cognitive Development, Neural Networks, Volume 23, pp. 1125-1134, 2010.

If you liked this article, you might also be interested in:

Robotic research: Are we applying the scientific method?

Repeatable robotics: Standards and benchmarks from frontier science to applied technology

Towards standardized experiments in human robot interactions

Gestures improve communication – even with robots

See all the latest robotics news on Robohub, or sign up for our weekly newsletter.

Frontiers in Robotics and AI is an open-access journal that provides thematic coverage on areas across robotics and artificial intelligence... read more

Andrea Del Prete Daniele Pucci Francesco Nori Francesco Romano Frontiers Robotics and AI humanoid robots iCub Jorhabib Eljaik Silvio Traversaro

Research & Innovation

Business & Finance

Health & Medicine

Politics, Law & Society

Arts & Entertainment

Education & DIY

Events

Military & Defense

Exploration & Mining

Mapping & Surveillance

Enviro. & Agriculture

Aerial

Automotive

Industrial Automation

Consumer & Household

Space

latest posts popular reported elsewhere

Robot companions are coming into our homes — how human should they be?

by

Adeline Chanseau

Flying Ring robot can fly on its side

by

Rajan Gill

ROSCon 2015 recap and videos – Part 5

by

Open Source Robotics Foundation

The dark side of ethical robots

by

Alan Winfield

Could RoboBees help save food supplies? (video)

by

Robohub Editors

Marty: the little walking robot that’s more than a toy

by

Alexander Enoch

The Drone Center’s Weekly Roundup: 8/8/16

by

Center for the Study of the Drone at Bard College

Interview: International Ground Vehicle Ground Competition (IGVC) winner on “Bigfoot 2” Husky UGV

by

Clearpath Robotics

Fredrik Gustafsson - Project Ngulia: from Phone to Drone

by

Audrow Nash

As Intuitive Surgical continues to shine, competitors are entering the fray

by

Frank Tobe

latest posts popular reported elsewhere

Hello Pepper: Getting started to program robots on AndroidAs Intuitive Surgical continues to shine, competitors are entering the frayThe dark side of ethical robotsWall-climbing robots create a carbon fiber hammock (with video, images)Farming with robotsSweep: a low cost LiDAR sensor for smart consumer productsROS 101: Intro to the Robot Operating SystemNAO Next Gen now available for a wider audienceFlying Ring robot can fly on its sidePros and cons for different types of drive selection

latest posts popular reported elsewhere

Prospector-1—first commercial interplanetary mining mission

Robotic gait training for kids with CP – it’s cool but does it work? – Faculty of Rehabilitation Medicine – University of Alberta

How will robots shape our future? (infographic)

The Washington Post will use robots to write stories about the Rio Olympics

The Rio Olympics will have some of the smartest sports cameras ever

Welcome to the Cyborg Olympics

Major Drone Maker Implements No-Fly Zones For Rio Olympics

Hackers Fool Tesla S’s Autopilot to Hide and Spoof Obstacles

MIT and DARPA Pack Lidar Sensor onto Single Chip

Government initiative gives Google the go-ahead to test delivery drones in the US | New Atlas

How Lockheed Martin’s SPIDER Blimp-Fixing Robot Works

Scientists have designed a robotic onesie that uses tracking sensors to help struggling babies crawl

This Company Just Got Permission to Land a Robot on the Moon

Robot Revolution: Intelligence In, Intelligence Out — THE Journal

Wave robot able to crawl, swim and climb with single motor – E & T Magazine

China’s Impending Robot Revolution

‘In robotics, the challenge is the application’

US military using ‘drone buggies’ to patrol Africa camps

New Surgical Robots May Get a Boost in Operating Rooms

Relax about robots but worry over climate change – FT.com

150th Episode Special

February 21, 2014

A dedicated jobs board for the global robotics community.

Senior Researcher in UAV Communications and Coordination - Lakeside Labs GmbHSenior Research Engineer - ConSol PartnersLead Mechanical Engineer – Robotics - Sealed Air Corporation - Intellibot RoboticsElectrical Engineering Manager – Robotics - Sealed Air Corporation - Intellibot RoboticsSoftware Engineering Manager – Robotics - Sealed Air Corporation - Intellibot Robotics